KGB headquarters (Taken from Crime Library)

Updated: Sunday, June 6, 2004 11:09PM

The Lives of the Cambridge Spies and the Project Known as

Venona

By Kyle Cai

KGB headquarters (Taken

from Crime Library)

At the mention of spies and counter intelligence agencies such as the M16 and the CIA, one would undoubtedly think of the James Bond films, or perhaps books by John LeCarre, and Graham Greene. Yet, with all of its gadgets, and actions, no fictional descriptions can capture the drama and the excitement of the Cambridge Spies. At the height of their careers, the four agents penetrated the highest reaches of British and American intelligence establishments. Despite their different characters and questionable actions, it is difficult to resist the temptation of glamorizing their dark and enigmatic lives.

Near the late 1920's, the NKVD (later known as the KGB) formed a plan to infiltrate the British intelligence establishments. The target, bright young college men, destined for careers in the Foreign Office or the intelligence agencies. Such men were carefully selected and meticulously cultivated. Open members of the Communist Party were excluded from the selection for they were too easily identified as security risks to Britain for their open radicalism. It was, as it turned out, a brilliant strategy.

The Cambridge Spies were composed of four such young men recruited by the KGB during their undergraduate years at Trinity College of Cambridge University.

Trinity College, Cambridge University (Taken

from Crime Library)

Before venturing any further, this would be a good place to unmask the cast of characters whose lives have intrigued so much of our imagination.

Anthony Blunt (Taken

from Crime Library)

Anthony Blunt: Tall, charming and arrogant, Blunt was a dedicated Communist, and a discrete homosexual. He was the grandson of an Anglican bishop, and the son of an Anglican Vicar. During the war, he served for the M15, a British agency similar to the FBI. He became the director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, for his specialty in the history of art. Later, he became the Royal Family's art advisor, and was even knighted in 1956. Out of the Cambridge four, Blunt had the longest active, undetected career as a spy, for about 30 years, until he confessed under a grant of immunity in 1964. In 1979, he was stripped of his knighthood after he was publicly declared a Russian spy by Margaret Thatcher. Until his death in 1983, he was the only one of the four to remain in Britain.

Guy Burgess (Taken

from Crime Library)

Guy Burgess: A flamboyant homosexual, Burgess was strikingly handsome and charming. At the same time, he was unpredictable, disheveled, and an intense alcoholic. He remained sexually promiscuous and predatory during his life time. Being the son of a naval officer, Burgess failed in attempting to follow in his father's footsteps. He had many very powerful friends, which aided him in his pursuits of secret information useful for the Soviets at the time. Burgess' career lasted around 12 years until he defected to Russia along with Maclean.

Donald Maclean (Taken

from Crime Library)

Donald Maclean: Much like Blunt, Maclean was tall and handsome. His father was at one point a member of the Parliament and Secretary of Education in the government of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. Another alcoholic (in addition to Guy Burgess), one time he was sent home from Cairo after a rowdy drunken episode. Because of his lack of nerves, both Philby and Burgess knew that Maclean would crack and confess under intense M15 interrogations.

Harold Adrian Russell Philby (aka Kim Philby) (Taken

from Crime Library)

Harold Adrian Russell Philby: Philby was also known as Kim, after the character in Kipling's jungle story Kim. He had been described as ingratiatingly smooth. In fact, like a chameleon he could be whatever the occasion demanded. The most intelligent of the four, Philby possessed incredible instinct as a spy. In his autobiography he had said that he was recruited by the NKVD (later KGB), and in turn he recruited Burgess and Maclean. Of course, the difficulty with Philby is that he cannot always be believed, and some have raised doubts about his recruitment and his recruiting. However, all four of them certainly knew each other well at Cambridge.

Philby's father, St. John Philby was at some point of his life a British spy, and diplomat. He had been critical of the British government, and extremely eccentric in nature. Kim saw very little of his father during his youth, but greatly admired him. A hyperactive heterosexual, Philby married four times, with several mistresses between each marriage. Both of his second and third wife were seduced by Philby while married to others, and left their husbands to marry Philby. After about a 23 year career, Philby defected to Russia in 1963. Since then, he continued to work for the KGB, as an instructor of agents almost till his death in 1988.

Now that we have become somewhat acquainted with the infamous four, their backgrounds and personalities, perhaps it is time to give a detailed account of what kind of information they dealt with, and how are they associated with the project known as Venona.

Burgess and Blunt contributed to the soviets many transmission of secret Foreign Office documents that had detailed descriptions of Allied military strategy.

Donald Maclean, during his tenure with the British Embassy in Washington DC, had been the main source of information to Stalin about communications and policy development between Winston Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt, and then later Churchill and Truman. Furthermore, his reports on the development and progress of the atomic bomb helped the Soviets estimate the amount of uranium available in the US. His position as the American-British-Canadian council on the sharing of atomic secrets helped the Soviet scientists to predict the number of bombs that could be built by the Americans. Along with information from other agents, Maclean's reports to his KGB controller helped the Soviets not only build the atomic bomb, but also how to estimate their nuclear weapons' relative strength against that of the US.

Kim Philby was assigned various tasks. During WWII, he transmitted the information that the Nazi secret code, "Enigma," was broken by his colleagues at the famous British decoding center at Bletchley Park. Philby, with his easy charms, quickly gained acceptance by his cryptanalyst colleagues. In his position in the M16, Philby was able to identify British agents in Russia. Not only did he have access to them, he was one of the instructors in espionage techniques for many.

Philby by far was the most active and the most impressive, considering the risks he took. Several times during his career, he was accused of being a mole in the M16. Each time he was always able to blunt their accusations by taking charge of their cases so he could divert suspicion from himself. Some have speculated that he could have even become the head of the Secret Intelligence Service. Shortly before his death, Philby said, "I truly was incredibly lucky all my life. In the most difficult situation when I was sure this was it, the end no way out, suddenly some stroke of luck would come my way. It was amazing how lucky I was... a lucky life."

(Picture taken from National Security

Agency)

During the 1940s and early 1950's, Philby was assigned to Washington, D.C., serving as liaison between M16 and the CIA. There he gained valuable information about what is now known as the Venona project. As a part of his official duty, he regularly received copies of summaries of the Venona translations.

Before going any further, let's look at the Venona project more closely.

On February 1, 1943, the US Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS, also known as Arlington Hall, after the Virginia location of its headquarters), a forerunner of the National Security Agency, began a small, and very secret program, later codenamed Venona. The goal of the program was to examine and exploit encrypted Soviet Diplomatic communications. These messages were accumulated by the SIS since late 30s, but had not been studied previously. The project was started by a young SIS employee, Miss Gene Grabeel.

Initial analysis indicated that five cryptographic systems were used by different subscribers. Further analysis showed that each of the five systems was used exclusively by the following subscribers:

1. Trade representatives, and the Soviet Government Purchasing Commission.

2. Diplomats, i.e., members of the diplomatic corps in the conduct of legitimate

Soviet embassy and consular business.

3. KGB, the Soviet espionage agency, headquarters in Moscow Residencies

(stations) abroad.

4. GRU, the Soviet Army General Staff Intelligence Directorate and attaches

abroad.

5. GRU Naval, the Soviet Naval Intelligence Staff.

From the beginning of 1943, the analysis of the traffic proved slow and difficult. However, in October 1943, Lieutenant Richard Hallock, a reserve officer who had been a peacetime archaeologist at the University of Chicago, discovered weaknesses in the cryptographic system. A breakthrough in the cipher system used by the KGB was made by Cecil Phillips through cryptanalysis. Despite Arlington Hall's extraordinary cryptanalytic breakthroughs, it was to take almost two more years before parts of any of these KGB messages could be read. Strong cryptographic systems like those in the Venona family of systems do not fall easily. In the summer of 1964, Meredith Gardner began to read portions of KGB messages that had been sent between the KGB Residency in New York and Moscow Center. Two years later, another KGB message was read, which contained a list of names of the leading scientists working on the Manhattan Project - the atomic bomb!

In 1947, an Arlington Hall report showed that the Soviet message traffic contained dozens, probably hundreds, of cover names, many of KGB agents. The Venona messages were filled with hundreds of cover names, designed to hide the identities of Soviet agents, organizations, people, or places discussed in the encrypted messages. For example, Kapitan was the cover name for President Roosevelt; Babylon was for San Francisco; and Enormoz was the name for the Manhattan Project.

Only a fraction of total messages sent and received were available to the cryptanalysts. The message were never exploited in real time. Of the message traffic from the KGB New York office to Moscow, about 50 percent of the 1944 messages were readable, and only about 15 percent for the messages in 1943. This was only true for about 1.8 percent of the messages from 1942.

In order to understand the difficult task of breaking the Venona code, it is important to understand the nature of and the way that the encryption worked.

The encryption of the message from the Soviets used a "one-time pad", a table of randomly generated numbers used to encipher numeric equivalents of words. Two copies of the pad were made, one used by the sender of the message for encryption, and one used by the receiver of the message for decryption. After it was used, the pad was destroyed to avoid multiple messages being encrypted the same way. The "one-time pad" system of encryption is known to be theoretically unbreakable, if used properly. Each pad is meant to be used for one time and one time only. Afterwards, it must be destroyed to avoid being used again. Furthermore the numbers on the pad must be generated in a completely random fashion, without any recognizable pattern or order.

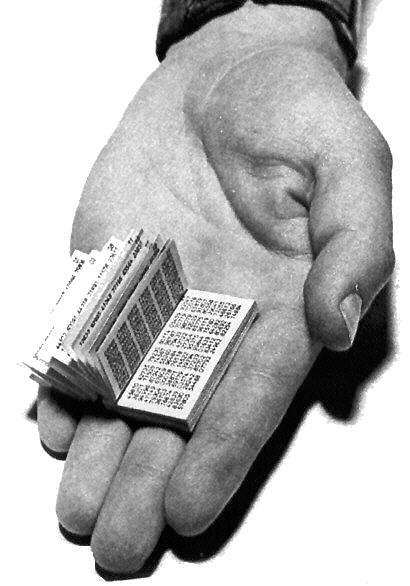

A one-time pad used by the Soviets (Taken

from Otto-von-Guericke-Universitšt Magdeburg, Denmark)

How did it fail?

Beginning in the 1940s, US and UK intelligence agencies were able to break some of the Soviet one-time pad traffic to Moscow, as a result of errors made near the end of 1941 in generating and distributing the key material. One suggestion was that the Moscow Center personnel were somewhat rushed by the German troops present outside of Moscow. This accident caused the Soviets to re-use one time pads years after they had originally been distributed to field agents in Britain. A pattern was discovered in some coded messages, and through a period of several years, other communications were slowly compromised.

Now that we have gained some understanding of the Venona project and crypto system used, the question becomes, how is it related to the Cambridge spies, and how did it change the course of their lives?

In 1949, Robert Lamphere, FBI agent in charge of Russian espionage, along with cryptanalyst from Arlington Hall, discovered that a member of the British Embessy was sending messages to the KGB. The code name of this person was "Homer." After a process of elimination, list of three or four men were identified as possible suspects. One of whom was Donald Maclean.

Through his position in Washington, Philby was able to obtain the information that Maclean was a suspected Soviet agent. This puts enormous pressure on the shoulders of Philby. If Maclean confesses, then it might lead to the unmasking of other Cambridge spies. Philby himself might be implicated for no other reason than his association with Maclean at Cambridge. During that period, Burgess had become more and more of an unpredictable heavy drinker. He was assigned to the British Embassy in Washington. Philby thought he should keep an eye on Burgess, so Burgess was allowed to stay in the basement of the apartment owned by Philby and his family. Concerned about Maclean's endangered state, Philby and Burgess designed a scheme in which Burgess would return to London to warn Maclean of the impending unmasking, without causing suspicion.

Sometime in the following weeks, as Burgess was driving to attend a conference in South Carolina, he managed to receive three speeding citations in a single day. The first two resulted in a release after his claiming of his diplomatic immunity. The third citation caused him to be detained by the police for several hours. This last event was communicated to the Governor of Virginia, and then the State Department, and then the British Embassy. Burgess was then soon recalled back to London.

The plan was for Burgess to visit Maclean in London and inform him his imminent exposure and necessary defection to Russia. Burgess, however, had received explicit instruction from Philby not to defect with Maclean. Arrangements were made for Maclean's defections by the Cambridge spies' KGB controller Yuri Modin, and the KGB Central demanded that Burgess escort Maclean behind the Iron Curtain.

On Maclean's Birthday, May 25, two days before he was to be interrogated, Burgess and Maclean fled to the coast, boarded a ship to France and disappeared.

Philby Assumed that Burgess would deliver Maclean to a handler, and that he would return. For some reason, the Russians insisted that Burgess accompany Maclean the entire way. Some suggest that perhaps Burgess was no long useful, but was too valuable to let him fall into the hands of the British.

After Maclean and Burgess fled the country, the British government reluctantly admitted that the two men had been Soviet spies. The Soviets on the other hand refused to acknowledge their services to the Russians. Burgess spent twelve years in the care of KGB, never learning Russian, indulged with a modest apartment, complete with state-sanctioned live-in lover. Though he expressed a desire to return to England, neither the Russians, who wouldn't let him return, nor the English, who had no wish to reopen the doors to an ex-Soviet agent, would support his repatriation.

Maclean on the other hand integrated himself into the Soviet system by learning Russian, and eventually serving as a specialist on economic policy of the west.

Back in Washington, Philby was surprised that Burgess defected along with Maclean. That placed Philby under suspicion since both the FBI and CIA were well aware that Burgess had been living with Philby and his family. From then on, Philby referred to Burgess as "that bloody man," and never spoke to him again. Even when Philby arrived in Russia in 1963, Burgess wished to see him as he was dying, but Philby would have nothing to do with him. Nevertheless, Philby was Burgess' principal heir.

Anthony Blunt had become a member of the Establishment, and, in a sense, a member of the Royal Household. Though all evidence pointed at Blunt's questionable past, the M15 did not want the Blunt case to become public. The only way to obtain a confession from Blunt, and to protect the reputation of M15, was to offer Blunt immunity from prosecution. A meeting was arranged for Blunt in which all the charges were outlined, and Blunt was offered immunity, to which Blunt said, "It is true." During the debriefings that followed, Blunt provided information about other spies that were either dead or already known to the M15 and M16. In 1980, he was stripped of his knighthood, and was forced to resign his Cambridge University Trinity College Fellowship.

Philby was buried with honors in Moscow, Burgess and Maclean were cremated and their ashes returned to England for Burial. Blunt, the perfect English gentleman, never left England, died of an heart attack in 1983, and was buried in his native country. Till their deaths, the Cambridge spies never received any money for their service, except a sum of money given to Philby during a period in which he was under severe financial stress.

Since then, many have attempted to give a complete account of the history and drama of the Cambridge spies. In spite of their efforts, there are still many dark corners, which we may never discover. But for the most part, the lives of these four men stretched our usual impression of international spies. They were not mercenaries. Their crimes were the most terrible, and their actions were despicable. Whatever the conclusion, the Cambridge spies, undoubtedly, go down as the greatest group of spies we have ever encountered.

Further information!!!!

The Venona Project from the hands of the FBI!!!

Actual documents from the Venona project!!

The Venona project from Wikipedia!!!

More information about Kim Philby from Wikipedia (link down at the moment)

Secrets, Lies, and Atomic Spies

Books you can find about the Venona Project:

Venona:

Decoding Soviet Espionage in America

Venona

Secrets: Exposing Soviet Espionage and America's Traitors

Venona:

The Greatest Secret of the Cold War

Books and films you can find about the Cambridge Spies:

The

Cambridge Spies: The Untold Story of Maclean, Philby, Burgess in America

My

Silent War: The Autobiography of a Spy

The Cambridge Spies (BBC mini-series

2003)